Welcome to Stuff Catalans Do.

Here, for easier reading, I’ve combined all the Stuff Catalans Do posts from April 2017 into one.

You can read the Intro here.

Do you have any Catalonia stories, anecdotes, clangers, to share? Please do so in the comments at the end of this post. You can also join in the comments on the individual posts (to access the original post, click on the title). I’d love to read your comments.

Andorra

Very long and very crowded duty-free shopping street running through the mountains between Spain and France. In fact, Andorra is a mini-country, capital Andorra la Vella, officially called the Principality of Andorra: the heads of state are two co princes: the president of France and the bishop of the border town of La Seu d’Urgell in Spain (a quaint arrangement that has endured since 1278).

Andorra has fabulous mountain scenery, trekking and hiking in the mountains, trout fishing, horseback riding, mountain biking, bird watching, and great skiing. The very first time I went there, dragged along reluctantly by ski fanatics from my intermediate English class, the one thing I remember – apart from sitting smoking on the nursery slopes gloating at all those people with their legs in plaster on the bar terrace below – was my great joy at finding Cadbury’s milk chocolate at the famous Pyrénées department store on the main drag. Back then, and for quite a few years, Andorra was the weekend trip of choice to get hold of imported foods, electric appliances, new tyres, car radios and other duty-free goodies.

And until recently, it was a tax haven. Alas, no more, thanks to pressure from the EU and the Savings Tax Directive. But income tax, sales tax etc in Andorra is still comparatively low.

And Andorra is the only country whose official language is Catalan. The Andorrans (who number 76.949 according to 2014 stats) also speak Castilian and French.

With the adoption of its constitution in 1993, Andorra consolidated its international legal status and was admitted to the United Nations, thereby giving Catalan an official presence in that august body.

Arròs

In my Catalan família política (in-laws), paella, the famous rice dish, wasn’t a thing. We just had ‘l’arròs’ – rice. Which was the Sunday and holiday barbecue of choice where Catalan men showed off their skills with the brases (charcoal embers).

“We used to go to a wonderful barbecue place at Coll de Jou (at 1460 metres one of the toughest mountain passes in Europe where we once had the excitement of watching the Tour de Catalunya flash past).

Never ever has food tasted so good, in the pine forests, surrounded by clouds of wasps, with stones in our paper cups to stop them blowing away […]”

I wrote in The Catalan Picnic Experience.

“[…] The air becomes fragrant with woodsmoke as the men get the fires going. They all have hairy paunches hanging over baggy bermudas, and they stand around in groups shouting and waving kitchen tongs and long forks. The women start early in the morning at home, preparing the squid and prawns, scraping and steaming open the mussels and clams, making the fish stock from the prawn heads and then getting it all into plastic containers and not forgetting onions, garlic, parsley, tomato, saffron, the rice itself of course and the big flat pan and…”

While paella valenciana purists and Jamie Oliver fans fight it out about what may legitimately be called a paella, Catalonia has a huge number of different rice dishes. Arròs negre (black rice) contains cuttlefish and squid. Squid’s ink is used to colour the dish (get it in little sachets from the fishmonger).

Catalonia also has its own official gourmet rice from the Ebro Delta with the Denominació d’Origen Protegida (the equivalent for foodstuffs of the D.O for wines).

B for Besòs, Bon profit and Botifarra

Besòs

One of the rivers that Barcelona lies between on the coastal plain, as opposed to having a river flowing through the city. You know those three tall chimneys you can see as you look up the coast in the direction of the Fòrum? They belong to the old Sant Adrià de Besòs power station – a monument to the industrial past of the area – and that’s where the River Besòs hits the sea.

But first let’s clear up a misconception: Besòs has nothing to do with kisses (Castilian besos). It has a written accent on the last syllable and is pronounced ‘beZOSS’. The most widely accepted etymology is the name Bissaucio, found in a document dating to 990, and meaning two willows, presumably referring to the vegetation on the river banks.

The Besòs flows through the industrial-belt towns of Mollet, La Llagosta, Montcada i Reixac, Sant Andreu (Barcelona) and Santa Coloma de Gramanet, originally providing irrigation for Barcelona’s crops. But with industrialisation, by the 1970s and 80s it had won the distinction of being the most polluted river in Europe.

It was cleaned up in the 1990s and and finally the Parc Fluvial del Besòs along the last nine kilometres of the river was created. Since then, abundant wildlife has returned to the area – otters, for example, which hadn’t been seen for 60 years. As a headline in La Vanguardia newspaper proclaimed in April 2013: ‘El Besòs, de cloaca a camino fluvial’ (The Besòs, from sewer to riverside walk).

Bon profit (BON prooFEET)

What you must say if you see people eating. And eating is an extremely serious business here. Like you pop round to the mechanic mid-morning to ask them when they can check out your dodgy brakes. All is silent. You step over bits of engine on the pavement, sidle in past all the cars with their guts out… no one around. Right in the back, they’re sitting round a folding table in their greasy overalls, they have a red and white checked tablecloth and napkins, and pa amb tomàquet and ham and sausages, and steaming tall glasses of coffee. You’ve intruded on a sacred ritual: l’esmorzar (breakfast). “Bon profit!” you say and sidle out again.

Botifarra

For many years I believed that the Campionat de Botifarra held in the mountain village where we used to spend our summers was a botifarra – i.e. sausage – eating competition. Honest! We lived outside the village and rarely took part in the activities, but I have to confess a sort of morbid interest in trying to imagine how many sausages you would have to stuff down and in what space of time. And why was it a separate event from the costellada – the lamb cutlets barbecue – which took place in the special barbecue area by the river? Years later I found out that botifarra was a popular card game – el joc de la botifarra. The botifarra group cooking and eating bash is called a botifarrada.

Whatever, botifarra (pronounced bootiFARRa) is the blanket term for sausages, both fresh (fresca) and cured (cuita or curada), all made with finely minced lean pork and seasoned in different ways: botifarra blanca, botifarra catalana, botifarra negra and bisbe (these two are a kind of black pudding).

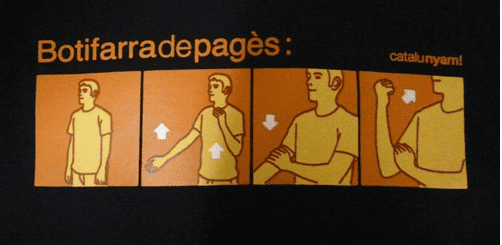

By the way, una botifarra is also a rude – well, obscene, says Diccionari.cat – gesture raising the arm and bending it. In a word: ‘up yours’.

C for Calçotada, Castellers, Català

Calçotada

The calçotada is the Catalans’ favourite gastronomic bash, traditional to the town of Valls and environs, and is the festive outing of choice from November to April. The last Sunday in January the streets and squares of Valls are taken over by sardana dancing, parades of musical bands, giants and bigheads, horse-drawn floats, sauce-making demonstrations, the calçot growers prize, the calçot eating competition…

But what exactly is this ‘burnt onion skin’ as one dubious newcomer put it?

The calçot looks (and tastes) like a cross between a leek and a spring onion, and is officially defined as ‘the replanted shoot of a fully developed white onion’.

It was discovered, apparently, by a farmer called el Xat de Benaiges who lived in Valls in the late 19th century. Tradition has it that he happened to toss the shoots of some shrivelled old onions onto a charcoal fire (because there was nothing else to eat?). But no one knows who developed the whole elaborate process of growing calçots: sow onion seeds, pull up the shoots after a few months, leave them in a cool dry place for several more months, cut off the tops, replant, and, as they grow, repeatedly cover the tender green shoots with earth. (In Catalan this action is called ‘calçar’, which means to put shoes on, hence calçot.)

Anyway, the calçots are cooked over a charcoal fire till their skins are charred, and served on curved roof tiles. You rip off the blackened outer skin, dangle them in a special sauce made with garlic, almonds and hazelnuts, tomato and mild red peppers, and then lower into your mouth. This is really messy, so you’re provided with a special bib.

And be prepared – the calçots are just the first course. Then come costelles (cutlets) and botifarres with allioli and doorsteps of farmhouse bread, all washed down with a local red.

I can’t think of a better way to get your fibre. Can you?

Meanwhile, you can check out everything calçots here.

Castellers

(Pronounced casteLLYEZZ)

I bet you never dreamt you would ever hear a pin drop in a public square in Spain. But in Catalunya be prepared for nail-biting suspense when the castellers – the castlebuilders – are in town. Their mind-boggling feats are an essential highlight of just about every festival and are reported on the news. And since 2010 they’ve been listed by Unesco as Intangible Cultural Heritage.

The castellers have their own wonderfully arcane terminology: the pinya (literally pine cone) is the base of the castle formed by a huge clump of interlocking people, the central part is the torre (tower), and the top part is the pom de dalt (top knob), which has three storeys. And there are all sorts of different castles, depending on the number of storeys and how many people form them. A quatre de nou (four of nine), for example, is formed by six storeys of four people each, plus the pom de dalt. The enxaneta is the tiny kid who scrambles up to the very top of the wobbling, tottering castell, raises a hand – the sign that the castle has officially been constructed – and slithers down again, fast. The helmets are a very recent concession to Health and Safety.

There are lots of colles castelleres (castlebuilder troupes) around Catalunya. Find their schedule here.

And watch the Xiquets de Valls troupe here.

Català

My late Catalan father-in-law once told an anecdote, in his usual deadpan way, that had us all rolling on the floor with laughter. During the Franco days, he was travelling from Barcelona to Madrid by train with a friend on business. Naturally, the two men were chatting in Catalan. In the same compartment was a Madrilenian lady with a lapdog. When the train reached Madrid, the dog began to bark in a frenzy of excitement.

“But of course!” proclaimed the lady. “He has heard barking, and he has replied.”

For the unprepared, the Catalan language (not dialect — the one gaffe you must never make unless you want to get up a Catalan’s nose big time) can come as a bit of a shock because it sounds quite different from Spanish: short, sharp and brusque.

On paper (or street signs), Catalan looks more familiar, like a cross between Spanish, French and Italian. But it’s a descendant in its own right of the Latin spoken in the northern Iberian peninsula during the Roman empire, and so a sister language to Spanish, French, Italian, Portuguese, Provençal and Romanian.

According to the Spanish Constitution of 1978, el català is co-official with castellano in Catalonia.

D for Denominació d’Origen Protegida

Hazelnuts from Reus, rice from the Ebro Delta, pears from Lleida, butter and cheese from Alt Urgell and La Cerdanya in the Pyrenees… olive oil from Siurana, Les Garrigues, l’Empordà… sorry, my mouth is watering too much to keep on writing.

These are some of the yummy Catalan foods boasting the Protected Designation of Origin of the European Union: right up there with the Gorgonzola, Feta, Parma ham, Melton Mowbray pork pies, Puy lentils, Kalamata olives and jamón serrano.

Of the three different seals for foodstuffs (not including wines and spirits which are under a special regime), the strictest is the Protected Designation of Origin for products closely linked to a sense of place discernible in the flavor of the food – that special ‘somewhereness’.

To qualify for a PDO, the product must have qualities and characteristics which are essentially or exclusively due to its region of production: i.e. climate, the nature of the soil and local know-how. It must also be produced, processed and prepared exclusively within that region.

But never mind the theory – just eat. It’s one of the great joys of living in Catalonia.

Bon profit!

E for Ebre, Esqueixada, Escalivada

Ebre

I knew that the Riu Ebre was Spain’s longest river. That its delta was an important wildlife reserve. For many years I also ‘knew’ that it was the boundary between Catalonia and ‘the rest of Spain’ (Aragon to the west and the Community of Valencia to the south). Except it isn’t. I honestly don’t know where I got this idea from: it must have been when the president-in-exile of Catalonia, Josep Tarradellas, returned from France in 1977, after Spain’s transition to democracy. He stopped off in Madrid to meet with Spanish authorities, then flew back to Barcelona on a plane bursting at the seams with journalists who were broadcasting live on the radio. As I remember, when they flew over the Ebre, we heard cava corks popping, cheering and clapping, tears of joy etc. The river’s lower course, in Catalunya and Eastern Aragon, had been the site of the longest battle in the Spanish Civil War, between July and November 1938, which led to the defeat of the Republican army and the fall of Catalonia (and exile for many thousands), so it certainly marks a spiritual and emotional frontier.

At 930 km, the Ebre is the longest river in Spain (well, yes, the Tagus is longer but is shared with Portugal), and in a largely dry country, the one with the biggest volume. In fact it gave its name (Iber, Iberus) to the Iberian peninsula. With its source in the Cantabrian mountains, the Ebre flows through Cantabria, Castile and León, La Rioja, Navarre, Aragon (notably through the city of Zaragoza) and finally Catalonia, where it empties into the Mediterranean via the Ebro Delta, a major wildlife reserve and natural park, a haven of peace.

Escalivada

One of the healthiest, tastiest summer dishes in the world: a salad of aubergines and peppers roasted on embers, of rustic origin. I once tried holding and turning the veggies with tongs in the flame of my gas hob to char the outer skin, but this was incredibly messy as the kitchen filled up with swirling burnt flakes. If you don’t have any embers lying around, the best compromise is to bake them in a fiercely hot oven. When they come out, wrap them in foil or newspaper and leave till cold. This makes them easier to peel, although the peeling process can be very messy too, especially the peppers, as you get those tiny sticky seeds all over the place as well as bits of skin. (I once saw a TV chef gently scrape the charred skin from a pepper with a clean scourer).

Serve escalivada as a garnish or salad, scattered with all i julivert (finely chopped garlic and parsley) and drizzled with extra virgin olive oil.

Esqueixada

(Pronounced eskeSHAHDduh)

There’s only one word for this salad of shredded salt cod with black olives, tomatoes, onions, and red and green peppers, dressed with olive oil: nyam! It’s so refreshing in summer, and so visually attractive with the contrasting red and green, black and white, glistening with golden olive oil. And it’s healthy.

With dishes like these, who on earth would ever want to eat fast food from a carton?

F for FC Barcelona

Having married into a family of cradle-to-grave Barcelona supporters, Football Club Barcelona, aka el Barça, is naturally one of the main threads in the tapestry of my life here. My sons were carted to the home matches at the Camp Nou by their dad and grandad almost before they could walk.

During summers (pre-Internet) in the mountains, I drove 15 kilometres of hairpin bends every day to buy the sports paper with its interminable transfer market sagas (by the time my sons could read and write, they were already walking football encyclopaedias.) When my father-in-law died without having made a will, his carnet del Barça (club membership card) caused more fratricidal strife and bitterness than any other piece of property.

But the one memory that eclipses all others and distils the essence of el Barça was the European Cup Final that Barça played at Wembley against Sampdoria on May 20th 1992. The city ground to a halt while every household was glued to the TV (Barça had never before won the European Cup, while arch rivals Real Madrid had won it six times: the bitter rivalry has deep roots in the history of 20th century Spain.) Tension rose to heart-attack level with the score at nil-nil. Extra time. Ronald Koeman has a free kick – and scores.

We all leap onto the balcony, yelling our heads off, singing, hugging each other: all around the courtyard families are cheering and waving. All night fireworks fizz and bang, horns honk. The whole of Catalunya is plunged into days of euphoria.

Two days after the match, our nephew got married. At the banquet, instead of making a speech, he produced a cassette recorder, raised his glass, and hit Play.

He’d taped the replay of Koeman’s goal from the radio.

The entire dining room exploded in a deafening roar of cheering, clapping, stamping, and the popping of cava corks. Again and again and again. Nothing in Barcelona’s awesome Olympics held in July that year would ever match that moment.

As the slogan goes, el Barça is more than a club (but you need a bit of history to understand why).

G for Gegants, Generalitat, Girona

Gegants

The giants of Catalonia are not the kind of horrid monsters of fairy-tale and legend that gave us childhood nightmares, but huge figures of men and women that are paraded around at just about every local fair and festival. Most towns and city neighbourhoods have their own giants, forming a great network across Catalonia, with competitions, meet-ups etc. They they are kind of like familiar locals: especially when you come across them lurking on a Sunday stroll in downtown Barcelona.

Generalitat

La Generalitat de Catalunya is the institution under which the autonomous community of Catalonia is politically organised. It consists of the Parliament of Catalonia, the President of the Generalitat de Catalunya and the Government of Catalonia. The institution goes way back to the 13th century, and you can read about its vicissitudes – a long history of abolitions and restorations – here.

And so, since the last restoration in 1978, Catalonia has had its very own huge lumbering bureaucracy. TV advertising campaigns assuring us again and again that the Generalitat is on our side are parodied mercilessly every week in TV3’s satirical show Polònia.

One sweltering summer in Barcelona, a musician friend of mine nearly went berserk with the clattering and whirring of air conditioners on the roof of a nearby building. Why didn’t he report them for noise pollution to the environment department? I asked, bursting with righteous indignation.

“They ARE the environment department,” he wailed. “Of the Generalitat.”

Girona

I love Girona. It’s quieter and less built-up than Barcelona (population 97,586 as of January 2015) but – to use a done-to-death word – vibrant. Especially since it became the film set for the powerful free city of Braavos in season six of Game of Thrones.

At the confluence of no less than four rivers – the Ter, the Onyar, the Güell and the Galligants – Girona (Roman Gerunda) was in a strategic position on the ancient Via Augusta that linked Iberia to Rome, and was repeatedly conquered, earning it the nickname ‘the city of a thousand sieges’.

Girona has a fabulous old quarter with a maze of cobbled streets, ancient city walls, one of the best-conserved Jewish quarters in Europe, 12th-century Arab baths, and a landmark cathedral with the widest Gothic nave in the world, reached via a stunning staircase of 90 steps. There are the picturesque Hanging Houses on the River Onyar with their colourful riverside facades, a ‘harmonious hotchpotch’ as one quaintly translated guidebook put it. There’s a bridge designed by Gustave Eiffel (who later built the Eiffel Tower). And lots more. And there are loads of festivals, in particular the Temps de Flors or Flower Festival held each May, with fabulous flower artworks displayed across the city.

And then there are the legends. Other cities have dragons, lions or eagles: Girona has flies. Sant Narcís (Saint Narcissus) is patron of the city, and his miracle happened in September 1286, when Girona was beseiged by the French. Even though the city surrendered without a fight, the French behaved atrociously: robbing, mocking and abusing the Gironans, sacking their churches and so on. The last straw was when they profaned the body of Sant Narcís and broke one of his arms. Whereupon giant flies emerged from his body and stung the French soldiers and their horses, who expired, twitching and writhing and, I imagine, foaming at the mouth.

“My grandad went to Cuba

On board the Català

The best warship

Of the overseas fleet.

The helmsman and the skipper

And fourteen sailors

Were born in Calella

Were born in Palafrugell.”

This is my literal translation of the first verse of the havanera El Meu Avi (My Grandfather) a song known by almost everyone in Catalonia. The song recounts the glorious demise of grandad and all on board while defending the remnants of the empire: audiences at village fairs sing along and wave white hankies.

Havaneres are typical sailor songs or sea shanties that were brought to Catalonia by fishermen and traders returning from Spain’s Caribbean colonies, in particular Cuba, in the 19th century. In 1898 war broke out between Spain and the United States (la Guerra de Cuba, also known as El Desastre del ’98) which culminated in the loss of Spain’s remaining overseas colonies (Philippines, Puerto Rico as well as Cuba) — the end of the empire.

But the music lived on, in taverns and now as the mainstay of fairs and fetes throughout Catalonia, along with cremat (hot rum), another Caribbean legacy. Named, obviously, after Havana, the capital of Cuba, havaneres are sung in harmony, accompanied by guitar, accordion, and bass, by men in striped jerseys. The havanera has its own dedicated festivals: the most famous one is held every July on the beach of Calella de Palafrugell, world havanera capital.

Watch, listen and sing El Meu Avi

Enjoy!

I is for IGP, Informàtic, Ioga

Indicació Geogràfica Protegida

Chickens (possibly headless) flapping and clucking along the runway amongst the aircraft: this was the image, still indelible, that popped into my head the first time I heard the name Pollastre del Prat. El Prat de Llobregat is the municipality on the Llobregat Delta where Barcelona’s El Prat airport was built, but the chickens (and capons) go way back to the area’s agricultural past (along with artichokes). Also known as Potablava (blueleg), the El Prat chicken is an autochthonous breed highly adapted to the Delta and is the only chicken in Spain to boast the blue and yellow Indicació Geogràfica Protegida (Protected Geographical Indication). This is given to products that are traditionally and at least partially manufactured (prepared, processed or produced) within the specific region and so acquire unique properties.

For the El Prat Chickens and Capons there’s a pile of highly detailed specifications about the colour and texture of feathers, feet, eyes and beak, but all you really need to know is that they are fed a diet of 80% grains and are allowed to live for a minimum of 90 days.

El Prat chickens are not the only Catalan foods with the real-deal IGP. For starters (in season) calçots from Valls. Serve your chicken with potatoes from Prades. Or just toast a doorstep of Catalan farmhouse bread (pa de pagès), rub it with real tomato, slather it with D.O P olive oil, and eat with llonganissa sausage from Vic or anchovies from Cotlliure (in French Catalonia). Wash it all down with a D.O wine like Priorat. For dessert, clementines from the Ebro or apples from Girona. And at Christmas time, turron from Agramunt.

Informàtic

L’informàtic is the computer guy, the tech, more often than not a shy, awkward, mumbling geek until he gets his hand on your mouse, when he instantly transforms into the quintessence of grace and zen-like concentration. And charges you a fortune for his time.

Ioga and Iogur

Where English, Castilian and most other languages have y-, Catalan has i-. Iaia (pronounced yaya) is grandma, granny. And here’s the one that still throws me every time: iot. No prizes for guessing.

J for Jaume 1, Joan, Jordi and Julivert

Jaume 1

Metro station in downtown Barcelona, named after Jaume el Conqueridor (James I of Aragon, aka the Conquerer). Pronounced JOWmeh (as in jowl) preeMEH, Jaume 1 (1208 to 1276) was the longest reigning Iberian monarch, King of Aragon, Count of Barcelona, and Lord of Montpellier from 1213 to 1276; King of Mallorca from 1231 to 1276; and Valencia from 1238 to 1276. This was long before the current territorial divisions (before Catalonia was a thing), when the Castilians under Ferdinand III and the Aragonese were taking back the Iberian peninsula from the Moors; Jaume 1 expanded the Aragonese territories to Languedoc, the Balearic Islands and Valencia, and also took the county of Barcelona from nominal French suzerainty and integrated it into the crown. Jaume is also highly regarded as a legislator and organiser. He compiled the Llibre del Consolat de Mar which governed maritime trade and helped establish Catalan-Aragonese supremacy in the western Mediterranean, and he was instrumental in the development of the Catalan language and literature. The Llibre dels fets is his quasi-autobiographical chronicle of his reign.

Joan

I once heard some visitor to Bcn on a tourist forum raving about Joan Miró and ‘her’ paintings. Back before the heady days of avatars and profile pics, I had a friend called Joan who was constantly mistaken for a woman by business correspondents. (He was also mistaken for a spy in the US, and he once hjiacked a public transport bus in Moscow, in the days of the Soviet Union, so admittedly he was quite a character). So he started using ‘John’ for his letterheads. Then he completely screwed up by having the brilliant idea of translating his street name – el carrer del Bisbe Sivilla – into English: The Bishop Siville Street. After which he was bemused not to get any replies to his letters at all.

Whatever, Joan is a man’s name, pronounced JooANN, equivalent to Castilian Juan, i.e. John, Johan (as in Johan Cruyff), all of which derive from Medieval Latin Johannes. The female equivalent is Joana.

Jordi

Probably one of the most popular names in Catalonia – after all, Sant Jordi is the patron saint (we’ll talk about him and his famous day when we get to S). Being a language lover, I decided to trace the name right back. Jordi, George, Jorge, Jürgen and a host of variants, go back to Ancient Greek Georgios. But there’s more: Georgios combines ‘ge’ meaning earth, land, ground (as in geography, geology) and ‘ergon’, meaning deed, work (as in en-ergy, ergonomic), so georgios is a person who works the land – a farmer. Despite having studied ancient Greek to a high level, I had honestly never realised this until now. Live and learn. (BTW the female name is Jordina).

Julivert

Pronounced jooleeVAIRT, this is parsley. All i julivert –garlic and parsley– is a typical traditional seasoning for meat, liver, fish, mushrooms and all sorts of dishes. You chop a couple of garlic cloves and a handful of parsley very fine and add it at the end of the cooking with olive oil. It’s a bit labour intensive, and now you can buy all i julivert ready-made, freeze-dried, deep-frozen… or you can do what I learned from a TV chef: blitz it with olive oil in the processor or hand blender and keep in a glass jar in the fridge. Add a spoonful to anything – especially anything tasteless. By the way, never buy parsley; get it for free at the butcher, fishmonger or greengrocer. Just ask for ‘una mica de julivert, sisplau’ . Keep it in an attractive jar with water and a pinch of sugar – it will perk up and stay pretty and decorative for days.

Catalans don’t really do K. It’s the 11th letter of the Catalan alphabet but is only used in words of foreign origin, from kafkià to kuwaitià. According to the rule book, the k- sound before –i and –e is represented in written Catalan by qu- as in quilogram, quilòmetre, quilovat, etc, but these weights and measures are often written with the more familiar international k. Oh, and Catalan Wikipedia is Viquipèdia.

You may also see ‘street’ k in words like okupa (squatter), as in Castilian. Girls’ names on the Catalan list at Viccionari are Karen, Kàtia, Katiuska and Kai

Kílian Jornet Burgada

The name Kilian is apparently of Celtic origin but this amazing mountain and skyrunner was born in Sabadell (near Barcelona) and raised in the high Pyrenees where his dad was a mountain guide and his mum a mountain sports instructor. He’s largely regarded as the world’s best endurance athlete. Kílian Jornet holds the fastest known time for the ascent and descent of Matterhorn, Mont Blanc and Denali. Watch him here in a water commercial, narrated by his mum.

Here is a full and dazzling list of Kílian Jornet’s achievements.

L for Llobregat

“The land of seven harvests” was how the agricultural area of the Delta del Llobregat (lyoobrehGATT) south-west of Barcelona was known historically, thanks to its great fertility, plentiful water and mild climate. Now, this area, the Baix (Bash = Lower) Llobregat, is mostly an ugly and cluttered sprawl given over to industrial estates and transport infrastructure like Barcelona’s port and airport, and urban development (several towns bear the name: San Boi de Llobregat, Cornellà de Llobregat, Sant Feliu de Llobregat, El Prat de Llobregat, and L’Hospitalet de Llobregat which is Catalonia’s second largest city by population). And yet… the local train trundling down the coast suddenly leaves behind the warehouses and drab logistics hubs and then, who knows why, stops. All around are row upon row of leafy vegetables. I watch a man ploughing a field right beside the track. This is the Llobregat Delta protected agricultural area that provides us with our weekly basket of productes de proximitat – local fruits and veg. The artichokes are particularly famous.

The Riu Llobregat, at 170 kilometres, is the second longest river in Catalonia (the longest is the Segre). Its source is in the Serra del Cadí up near the French frontier. On its way down to the Med it flows past the iconic jagged mountain of Montserrat and through the town of Martorell where the ancient Roman Via Augusta crosses the river on the impressive Devil’s bridge, which dates from the High Middle Ages in its current form.

A stone’s throw from the city, too, is a haven for birds and birdwatchers. The Natural Spaces of the Llobregat Delta (Espais Naturals del Delta del Llobregat) is a network of protected areas established in 1987 on the right margin of the river that have been declared a Special Protection Area. This is a strategic point on the western Mediterranean migration route between Europe and Africa. More than 360 species of birds have been sighted on the Delta, one of the largest numbers of species seen in the entire Iberian Peninsula. And all within Barcelona’s metropolitan area.

M for Mar i muntanya, Mató, Montserrat

Mar i muntanya

‘Sea and mountain’ is a type of dish that combines ingredients typical of mountain areas (meat, sausages, game etc) with fish and seafood, as in arrós mar i muntanya

For example:

- pollastre amb llagosta – chicken with lobster

- pollastre amb escamarlans – chicken with crawfish

- calamars farcits de carn – squid stuffed with meat

- rap amb cansalada – monkfish with bacon

- galtes de porc amb sípia – pork cheeks with cuttlefish

Also, the concepts of mar and muntanya are key to finding your way around Barcelona, which we actually managed to do long before GPS or Google maps. The first time I looked at a Google map of Barcelona, I got completely dizzy – it made no sense. When visiting parts of the city I know less well, I usually get completely disoriented. How to get home? Where to find the bus stop? ‘Just tell me which way the sea is,’ I wail. “On és el mar?”

From the old A-to-Z of Barcelona I bought when I first arrived to the big paperback guide distributed by the Ajuntament in the 1990’s to the online one at Bcn.cat Barcelona’s layout is stylized like this: the sea is a straight horizonal line across the bottom of the page. The horizontal streets are parallel to the sea, and the vertical streets perpendicular. So, down is mar, up is muntanya. Sideways it’s the two rivers: Besós or Llobregat. So when directing someone to the Pedrera, Passeig de Gràcia 92, you’d say: it’s on the corner of Passeig de Gràcia and Provença. Which corner? Muntanya, Besòs.

BTW, the Ajuntament map is incredibly useful because there’s are dropdown menus on the left for you to put all sorts of stuff on it – bus stops, Metro stations, traffic direction, car parks, pharmacies, city wifi hotspots… and lots more.

Mel i mató

Mató cheese drizzled with honey (mel) – a popular traditional Catalan dessert. Even better with a few strawberries or walnuts. Mató is a soft fresh cheese made from cow or goat milk, no salt added, similar to ricotta or curd cheese. The mató from Montserrat is particularly well-known. You can use mató for any of those recipes that require fresh cheese, mascarpone, ricotta, etc.

Montserrat

One of the things I found most odd when I first came to Barcelona was the very common name Montse. Okay, so Montse was short for Montserrat, but why were half the women in my English classes called ‘jagged mountain’?

La muntanya de Montserrat, just 59 kilometres from Barcelona, is Catalunya’s number one landmark, an amazing ensemble of crags and peaks visible for miles around. High in its folds is a Benedictine monastery containing the sanctuary of the Virgin of Montserrat, a Black Virgin, also known as ‘la Moreneta’ (the little dark-skinned one aka black madonna).

Identified by some with the location of the Holy Grail in Arthurian legend, this is the spiritual heart of Catalunya, and a pilgrimage centre to which football teams, athletes and assorted Catalans ascend (ideally barefoot) when their prayers have been answered by the miracle‑working Virgin (the patron saint of Catalonia, hence the millions of Montses). The age and origin of the wooden statue itself is shrouded in mystery.

Montserrat is also a paradise for hikers, climbers and the city‑weary: a funicular takes you far away from the tourist kitsch around the monastery to the top, where you can wander around in the sun, pick thyme and lavender, and gasp at the views (you can see Mallorca on a clear day).

And for your pub quiz: The Caribbean island of Montserrat was named after the mountain by Christopher Columbus in 1493.

If you love being made to jump out of your skin while strolling peacefully through your local square, if dosing your dog with valium is your thing, or locking yourself in with all the windows closed on a hot summer night, then you will positively adore the Nit de Sant Joan – St John’s Night – a.k.a. Nit de Foc or Night of Fire.

This festival marks the summer solstice and is celebrated throughout Catalonia on the night of 23 -24 June which, you may be protesting, is actually two days after the solstice: the Catholic Church made this most pagan of festivals coincide with the date of birth of St John the Baptist.

Fire is the central element – bonfires, firecrackers… any restrictions on the sale or use of which are not very stringently enforced, to put it mildly: kids throw them around in public places for days or even weeks before. Years ago, piles of old armchairs and dressers, tables and beds would grow in public squares and crossroads: until Health and Safety stepped in, bonfires, the big feature of Sant Joan, were lit right in the heart of the city. But you still have impressive formal firework displays – and the revetlla, the street party. In seaboard towns and cities, revellers wind up on the beach at sunrise – the thing goes right back to sun worship. 24 June, of course, is a public holiday.

So much for the #grumpyoldwoman take on Sant Joan. Anything good? Well… there’s the Coca de Sant Joan, a large oval confection filled with massapà (marzipan) and decorated with fruites confitades and pinyons (crystallized fruits and pine nuts), eaten at the revetlla and washed down with cava.

Here’s a coca recipe in English from the famous Barcelona pastisseria Foix de Sarrià. I’ve made it and it’s good.

O for Oli d’oliva and Oliveres mil.lenàries

Oli d’oliva

Liquid gold… healthy Mediterranean diet… absolutely delicious. And the Catalans do no less than five Denominació d’Origen Protegida extra virgin olive oils: Les Garrigues, Siurana, Baix Ebre-Montsià, Terra Alta, and l’Empordà. Nothing more to say except the over-the-top ‘I would die without it.’

Oliveres mil.lenàries

Some of the oldest olive trees in the world live in Catalonia, in the south of Tarragona province near the Riu Ebre. A couple of years ago, researchers from Madrid Polytechnic dated a listed monumental tree called La Farga de l’Arión to around 314 A.D, when Constantine ruled the Roman Empire, which included what we now call Spain. This makes the tree, located in the municipality of Ulldecona, 1703 years old, the oldest in all of Spain and possibly in the world. If only it could talk!

For an olive tree to be considered mil.lenària (literally one thousand years old; more generally, really really ancient), the diameter of its trunk measured at a height of 1.3 metres from the ground should be at least 3.6 metres: La Farga de l’Arión measures a whopping eight metres. In fact more than 4,400 olive trees in the area tick the boxes, and apparently there are even more out there that haven’t yet been located.

Since 2011, thirty-five of these amazing trees have been protected within the Museu Natural de les Oliveres Mil·lenàries de l’Arión. And, even more amazing, they still produce oil.

From north to south, from east to west, the Catalans do mountains big time, and Els Pirineus (pronounced PeereeNAYoos) are the biggest of the lot. You probably know that they form a formidable natural barrier between France and Spain, and are jammed with ski slopes, hiking routes, all manner of sports and outdoor activities, mountain lakes, horses, natural parks, Romanesque churches tucked away in tiny villages…

But do you know how they got there in the first place?

Thousands of years ago, in the place we now call the Pyrenees, King Tubal had a beautiful daughter, Pyrené, who was desired by many men. But Pyrené had a secret relationship with Hercules, the Greek hero. When Tubal found out, he banished Hercules. Pyrene wandered around inconsolably in the forest.

One day, Geryon, a horrible three-headed monster, tried to abduct Pyrené. She escaped his clutches but the enraged Geryon set fire to the forest to flush her out. An eagle watching the drama informed Hercules who came rushing back, only to find Pyrené breathing her last. Heartbroken, he buried her, building a mausoleum of huge rocks over her grave – the Pyrenees.

When I first came to Barcelona, when Spain was still a police state, I taught English at a school in a stately building on Rambla Catalunya, on the floor above what was then the Moroccan Consulate. One evening we heard a commotion outside and stepped out onto the narrow balcony: a handful of demonstrators were straggling down the central walkway, waving Polisario placards (the movement for the liberation of Spanish Sahara). They stopped opposite our building chanting “¡Marruecos asesino!”

“Bah!” scoffed my students. “Són quatre gats.” Few people.

And then flames whooshed up as a Molotov cocktail exploded on the Consulate balcony below. We scrambled inside and slammed the french doors shut. The director’s wife rushed in telling us in panicky broken Spanish to stay put, while black smoke billowed up the stairwell. But quite soon we were able to leave; I freaked out, to be revived in the local bar. A colleague recounted how a demonstrator had burst into his class and sat down, followed by the police. Poker-faced, my colleague – and the rest of the class – had passed him off as one of the regular students. From then on, our building was guarded by a couple of policemen with submachine guns.

And the expression ‘quatre gats’ was indelibly burnt into my memory.

I later learned that quatre is the Catalans’ favourite number for talking dismissively or disparagingly about anything: at best, not a big deal, at worst, pathetic.

- a quatre passes = four steps away = very close by

- quatre duros (o quatre rals o quatre xavos) = four cents = cheap or of little value

- només són quatre gotes = it’s only four drops (of rain) = it’s just drizzling a bit

- només té quatre pèls = he only has four hairs = he hardly has any beard or he’s almost bald

- dir quatre coses = say four things = tell off, give a piece of your mind

- quatre fulles = four leaves = a few bits of lettuce or herbs

Els Quatre Gats is also the name of the emblematic Modernista cafe in Barcelona’s Gothic Quarter that opened in 1897, a bohemian hangout for the artists and intellectuals of the time including the young Picasso. Recently it featured as a location in Woody Allen’s film Vicky, Cristina, Barcelona. And this year sees its 120th anniversary. It’s also the 150th anniversary of the birth of Puig i Cadafalch who designed the building (the Quatre Gats is on the ground floor).

It really was difficult to decide what to post for R. Top of the list was Reus, the city, basically so I could give its pronunciation (having heard it mangled so often): RAYoos. Then there’s rambla… rauxa… the Two Rogers (Roger de Llúria and Roger de Flor)… Anyway, yesterday I was watching our latest celebrity hipster TV chef make pigs trotters – not my favourite dish to be honest – when he said, with his signature wicked grin: “and now a good dash of ratafia (rattaFEEa) — to make it really Catalan.”

Bingo.

Jacint Verdaguer (one of the greatest Catalan poets, whom we’ll meet when we get to the letter V) tells this story:

Once upon a time, three bishops, from Vic, Barcelona and Tarragona, met for a regional council in a farmhouse somewhere in Catalonia to thrash out an important issue. Once they had reached an agreement and signed the relevant papers, they asked the farmer to bring them a drink. The farmer produced a big bottle of homemade liqueur and poured three glasses. The drink was new to the bishops, and they loved it.

“This is really awesome,” they said. “What is it?”

“It’s a drink we make here,” said the farmer.

“Doesn’t it have a name, man?”

“Not that I know of.”

“Right, then,” said the bishops, “we’ll find our own name for it. One that marks our agreement. How cool would that be?”

The three bishops had a think, then one of them yelled: “Got it! Rata fiat!”

(The expression ‘rata fiat’ is Latin for ‘it is ratified’).

Whatever. Some linguists believe that the word ‘ratafia’ is Creole, imported via French from the French West Indies, where in the 17th century the indigenous people used the name ‘tafia’ for rum made with sugar cane liquor macerated with fruit. This word features in a 1675 text from the island of Guadalupe.

Anyway, in Catalonia ratafia is made from alcohol (aguardiente) mashed with fruits, fresh walnuts, a variety of herbs, lemon peel, cloves, cinnamon and nutmeg. Many other herbs and spices may be used and sugar is often added for a thicker, sweeter, drink. As ratafia was traditionally made at home by farmers and other country people, there is no one master recipe: whatever fruits and herbs were on hand would be thrown in. Interestingly, herbs picked on the Nit de Sant Joan are believed to have magical properties and to bring good health and good luck, so ratafia is typically made then. The bewitching concoction is left to macerate for at least 40 days outdoors, where it gets both sun and shade.

‘Ratafia catalana’ has an Indicació Geogràfica in the category of Spirits. It’s usually drunk as an aperitif and also goes well with ice cream, cakes and biscuits and other desserts. I don’t drink alcohol, but I read that ratafia is “full of different tastes hidden within the depths of the liquid and allows the drinker to experience a little piece of the Catalan forests.”

The Catalans take their food and drink extremely seriously, and ratafia has its own dedicated fairs and festivals packed with tastings, competitions, workshops, herb-collecting walks, you name it. All is revealed at the website of the – wait for it – Ratafia Brotherhood – la Confraria de la Ratafia.

And if you really fancy making Catalan pigs trotters, you’re welcome to go here.

Over the years, I’ve written about Sant Jordi many times, so this is a mash-up of several oldish pieces.

El dia de Sant Jordi is a standout day in Catalonia, a not-to-be missed blend of fun and romance, culture and the hard-headed business sense that is said to be so typical of the Catalans. Sant Jordi (St George) is the patron saint of Catalonia and his day, 23 April, which is also the anniversary of both Shakespeare’s and Cervantes’ death (although this is now disputed) is celebrated by giving gifts of books and roses.

What makes Sant Jordi such an inspired combination of money-making, culture and entertainment is that it’s not actually a public holiday, so everyone is helplessly sucked in as they go about their usual business. Publishers save up their Big Launches for 23 April, booksellers rub their hands in excitement and organize VIP signings. All the bookshops set up stands in the streets and squares complete with buckets of red roses. Literary supplements roll off the presses. It’s a field day for journalists and chat-show hosts, too, with round-the-clock live TV coverage. The hawkers and panhandlers make a killing selling roses. And there are charity events, like massive book collections for hospitals. And discos and shows, dances and parties, fireworks and raffles.

If we really must talk in cliches, then the Catalans have clearly added a whole new dimension to the expression ‘laughing all the way to the bank.’

I don’t think much has changed, except for the advent of digital roses. Pity we can’t smell them. Anyway, if you’ve survived the crowds today, tell us what you think.

T for Tombatruites and Truita

Making a truita (trooEETeh) de patates (Spanish omelette) is dead easy. You fry the diced potatoes in olive oil till soft. You beat the eggs in a bowl, with salt. You add the eggs to the pan and cook the mixture on one side. And then you flip it over – and end up with a half-cooked mess splattered all over the hob, the floor, and your shoes, and hot oil dripping down your arm.

You need a tombatruites

The tombatruites (literally omelette-flipper) is a large glazed earthenware plate, with a large knob on the underside specifically designed to grasp while you deftly turn over those huge six-egg jobs that are too big and heavy for any of your normal plates. And it doubles as a nice platter for serving tapas, canapes, cakes and so on.

In my early days in Catalonia I was completely bamboozled by a conversation between friends about ‘truites de riu.’ I knew that truita meant omelette (Castilian tortilla), but what the hell was a river omelette? Only much later did I find out that una truita de riu is a trout.

From ancient Iberian settlements in the north to rock art and ancient olive trees in the south, the history of Catalonia goes way back.

Ullastret (oolyaSTRET), a town in the Baix Empordà region (inland from the Costa Brava), is home to the largest Iberian settlement so far discovered in Catalonia, dating to around 550 B.C. With its towering walls, the city served as the capital of the territory that ancient authors ascribed to the Iberian tribe of the Indigets or Indikets, and was the centre of an important trade with the Greek city of Empúries. The archaeological remains tell us a lot about the Iberians’ way of life – their agriculture, livestock farming, mines and quarries, urban planning and so on.

And then there are the severed heads. Two skulls that had apparently been nailed to a wall had been found in 1969. In 2012 three more were unearthed in an excellent state of preservation, two of them with enormous nails included. They are assumed to have been taken as trophies of war. But the really interesting thing, as the archaeologists explain, is that because the Iberians cremated their dead, it’s very difficult to find remains that can tell us what they ate, what they died of – and what they looked like.

So a facial reconstruction was made from the best preserved skull – and apparently the Iberians didn’t look too different from us.

Of course you can can visit the settlement. And you can also watch a video (with Hollywoodesque music) showing the reconstructed city.

And then there’s the making of the reconstruction. Interestingly, videogame software tools were used rather than the usual architectural tools, which gives a more immersive experience. Recreating texture was a particularly important aspect of the work. And they’re working on making it more interactive: “To bring our heritage to life in a contemporary way which will better engage younger generations.”

Ulldecona

You may never have heard of Ulldecona (unless you read the post about ancient olive trees) but quite recently it’s been in the Spanish news as, to paraphrase, the tiny town that’s a crack factory. Not the drug, you understand, but a ‘manufacturer’ of star players (‘cracks’) for the Premier League. Apparently this town of less than 7000 inhabitants has produced no less than two local whizz kids, Oriol Romeu and Aleix García, who are now playing for Southampton and Manchester City respectively. No, I had no idea either.

Anyway, this last place before the border with Valencia, as well as being one of Catalonia’s most important medieval towns with its hilltop castle, has a much more lasting claim to fame: its cave art. The Cave Art of the Mediterranean Basin in the Iberian Peninsula is made up of 757 sites with paintings and was awarded World Heritage status in 1998. Together they form the largest collection of cave paintings in Europe. In Catalonia these include the hermitage shelters (shallow cave-like formations) in the Sierra de Godall mountains near Ulldecona which contain a stunning 386 paintings depicting archers, animals and other hunting related scenes.

Check Ulldecona out here.

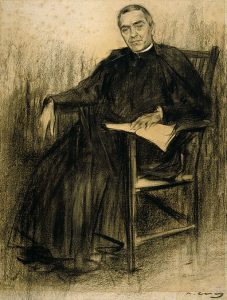

Verdaguer

Maybe the first thing that springs to mind is that metro station in Barcelona whose name you can’t pronounce. The Verdaguer monument is close by, unreachable in the centre of a major road intersection. In fact Catalonia is jammed with streets and squares, schools and other institutions (and monuments) commemorating Jacint Verdaguer.

So who was this obviously iconic Catalan?

First, though, the pronunciation: VairduhGEH. Also known affectionately as mossèn Cinto – Father Cinto – moossen SINtu (yep, he was a priest.)

Jacint Verdaguer i Santaló (1845 – 1902) is regarded as one of the greatest poets of Catalan literature and a leading literary figure of the Renaixença, a cultural revival movement of the late Romantic era. He was a prolific writer who gave the Catalan language the push it needed to rise from the ashes.

According to a word cloud now gracing a wall inside the Vil.la Joana, the summer house in the hills outside Barcelona where Verdaguer died of tuberculosis (recently reopened as the Casa Verdaguer de la Literatura), ‘amor’ (love) is the word Verdaguer used most often, followed by ‘Maria’, ‘flor, ‘Jesús’ and ‘Sant’. His writing spanned epic and lyrical poetry, narrative prose and travel writing (at one stage he worked as a priest on transatlantic liners), had an enormous popular influence unrivalled in his time, and some of it has been translated into lots of languages. His most famous works were the epic poems, the award-winning ‘l’Atlàntida’ (fragments of which were later set to music by Falla) and ‘Canigó.’

His death was mourned by all Catalonia and his funeral was one of the country’s largest ever public outpourings of grief.

And yes, I’d love to dig deeper into what made him tick.

Vermut

The first (and last) time I went to a Sunday brunch here, I had what felt like gastric jet lag. I mean, why would you do brunch when you can have a late breakfast of delicious pastries and coffee, and then, before your late, long, lazy lunch, the vermut?

Yes, vermouth, of course. But in Catalonia ‘fer el vermut’ means much more than just knocking back a glass of the stuff. It’s a beloved tradition, an eminently social occasion, especially on Sundays (originally after mass): it’s a pre-lunch drink and salty snack with friends and family, on a bar terrace, in a restaurant, or at home.

Traditionally, adults drink vermouth and kids non-alcoholic drinks. Olives are a must – and you may get anchovies, crisps, salted almonds, clams and so on. So get yourself to a tourist-free town or neighbourhood on a sunny Sunday (late) morning and – salut!

W is not really a ‘native’ letter in Catalan. The only words in the W section of the dictionary are those of foreign origin, from wagnerià through waterpolo and watt to whisky to wulfenita and wurtzita. I misread this last one as wurstita and, thinking it was some kind of sausage, I checked it out (I do love research). In fact wurtzite is a mineral, first described in 1861 for an occurrence in a mine in Bolivia and named after the French chemist Charles-Adolphe Wurtz. Nothing to do with Catalonia but learning is fun, right?

Now of course wifi and webcam are accepted words.

But the Catalans don’t do Wikipedia: it’s Viquipèdia.

Did you freak out when you saw this word? People tend to when they see a piece of text in Catalan because of the liberal sprinkling of ‘x’ s, and they tune out thinking that it’s a weird and unpronounceable mish-mash.

In fact xiuxiueig is one of Catalan’s most lovely onomatopoeic words. Repeat after me: sheeoo-sheeoo-WEDGE. It means whispering. From the verb xiuxiuejar – sheeoo-sheeoo-wedg-A – to whisper.

The letter x may represent three different sounds, the first of which is the freak-out one. It’s pronounced like English ‘sh’, okay?

So: no prizes for getting these right: xampú, xèrif, xocolata, Xile, Xina.

Xarxa (sharsha) is a network.

And in xip and xat English ch- has been reduced to sh.

In the middle of a word the sh sound is written as ix, the most obvious example being la Caixa – la casha. So, the famous poet J.V. Foix and his family’s emblematic pastisseria Foix de Sarrià is: Fosh.

There are also quite a few words where Catalan x corresponds to Castilian j (pronounced ‘ggghhh’) so in fact the Catalan versions are easier to say: Xavier (Javier), the Valencian towns Xàbia (Jávea) and Xàtiva (Játiva), and the Christmas turron from Xixona (Jijona).

In international words like taxi, it’s pronounced as in English.

And it’s pronounced –gs in words like examen (exam), exemple (example) and exercici (exercise).

As a letter of the alphabet, it’s pronounced ‘iks’. But there’s no need to to get tongue-tied with raigs X if you need an X-ray. Just say radiografia.

My hefty (dead-tree) Diccionari de la Llengua Catalana has only one word with Y – yperita (the y is pronounced ‘ee’) It doesn’t even have its own page, but is lumped together with Z.

So I could simply miss Y out, especially as I’ve already overshot the ‘official’ April A to Z Blogging 26-day schedule based on the English alphabet. But I’m also a bit obsessive, so… yperita is the chemical agent iperite, aka mustard gas: the French name ypérite comes from its usage near the town of Ypres in Belgium in the First World War. Interestingly, here Catalan keeps the French y- unlike English iperite, Spanish iperita, Italian iprite, although according to the (more up-to-date) online version of the Diccionari, iperita is also used.

As always, live and learn.

And if you’re wondering about more everyday items like yoga and yogurt, then remember – Catalans write them with initial I.

Ah – the joy of research. To tell you the truth, I was stumped. There aren’t that many Z-words in Catalan, at least not native words. Most are international ones from Greek and other languages – like zebra, zènit, zoo, zombi, zona – and country names and their adjectives like Zàmbia and zambià, Zaire and zairès. (If you’re a real word nerd there’s a list here). There’s also Zona zàping, a weekly roundup on Catalan TV of sports fails – people falling off bikes, skiing into trees… you know the kind of thing.

And then, right at the bottom of the list, was zumzeig (zoom-ZEDGE). Aha! The delightful onomatopoeic counterpart to xiuxiueig. I discovered it’s from the verb zumzejar which means to oscillate or move up and down (like waves). And, more colloquially, zum-zum is a humming noise – as of bees or a crowd of people.

And then I found something new and interesting, a fitting way to end this blog series:

Zumzeig is Catalonia’s first cooperative cinema. “A committed, activist, non-profit cultural project, with an original-version program along with other cultural activities.” I translated that for you from their webpage, but from now on you’re on your own. Enjoy!

4 Responses

I suggest to please add Correfocs to C as well! For a person like me, the craziest/best stuff the land has to offer!

Thanks for the suggestion, Omair. Will add it to the list for forthcoming posts. 🙂

This is great stuff. Really helpful! Don’t forget S for Sardana.

Glad you like it, Robert. Sardana is definitely on the list.